The Earth’s damaged ozone layer, essential to preserving life on the planet, is expected to be fully recovered within a few decades. This is the latest achievement of a global campaign by governments to cease using chemicals that had been depleting the upper atmosphere’s most important layer.

According to a new United Nations-backed assessment, the Earth’s ozone layer is on course to fully regenerate within decades as ozone-depleting chemicals are phased out worldwide.

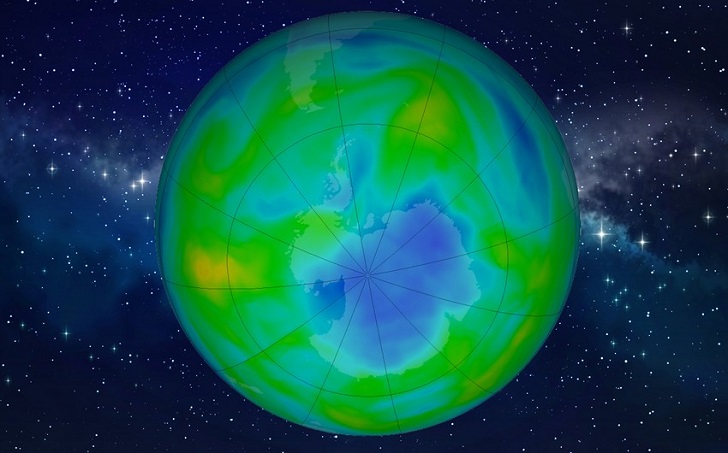

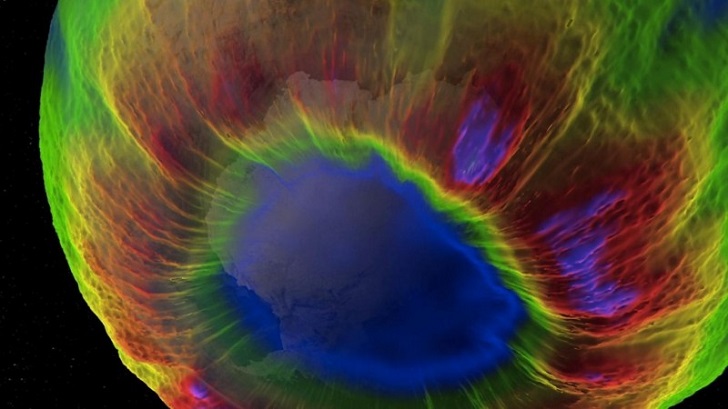

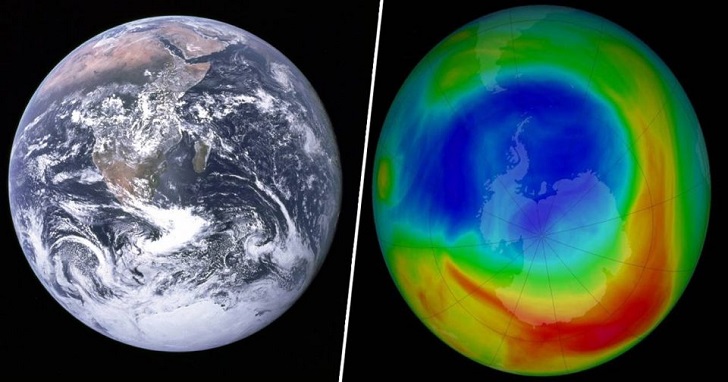

The planet is protected from dangerous UV rays by the ozone layer. But since the late 1980s, ozone-depleting compounds like chlorofluorocarbons, sometimes known as CFCs,] – frequently found in refrigerators, aerosols, and solvents – have raised concerns about a hole in this shield.

On track to full recovery

According to a United Nations-backed group of experts, the Earth’s protective ozone layer is expected to rebound within four decades and close an ozone hole first spotted in the 1980s.

The scientific assessment’s conclusions, which are released every four years, are in line with the landmark Montreal Protocol of 1987, which forbade the manufacturing and consumption of substances that deplete the ozone layer of the earth.

The phase-out of approximately 99% of the prohibited ozone-depleting compounds is confirmed in the quadrennial assessment report of the UN-backed Scientific Assessment Panel to the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances.

Thus, the Montreal Protocol has been successful in protecting the ozone layer, resulting in a noticeable recovery of the ozone layer in the high stratosphere and a reduction in the amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation that humans are exposed to.

If present policies are followed, it is anticipated that the ozone layer will return to 1980 levels (before the ozone hole appeared) by 2066 over the Antarctic, 2045 over the Arctic, and 2040 for the rest of the planet.

Particularly between 2019 and 2021, changes in the Antarctic ozone hole’s extent were mostly caused by weather. But since 2000, the size and depth of the Antarctic ozone hole have been gradually increasing.

Decline of CFC-11

According to Martyn Chipperfield, a professor at the University of Leeds and member of the scientific panel, the recent decline in levels of the chemical known as CFC-11, in particular, which until recently had been observed at higher-than-expected levels and traced to China, is evidence that societies can work together to address a perplexing environmental problem.

CFC-11 was created for the first time a century ago and was once widely used as a refrigerant and in foam insulation. CFC-11 and related substances, generally known as chlorofluorocarbons, deplete ozone, which protects people, plants, and animals from UV radiation from the sun that can cause skin cancer and other problems.

The Montreal Protocol, a significant environmental agreement that went into force in 1989, forbade the use of chlorofluorocarbons.

Ozone levels between the polar regions should return to pre-1980 levels by 2040 if nations maintain their prohibitions on chlorofluorocarbons and other pollutants. By 2045 in the Arctic and roughly 2066 in Antarctica, ozone holes, or areas of higher depletion that commonly emerge near the South Pole and, less frequently, near the North Pole, should also recover.